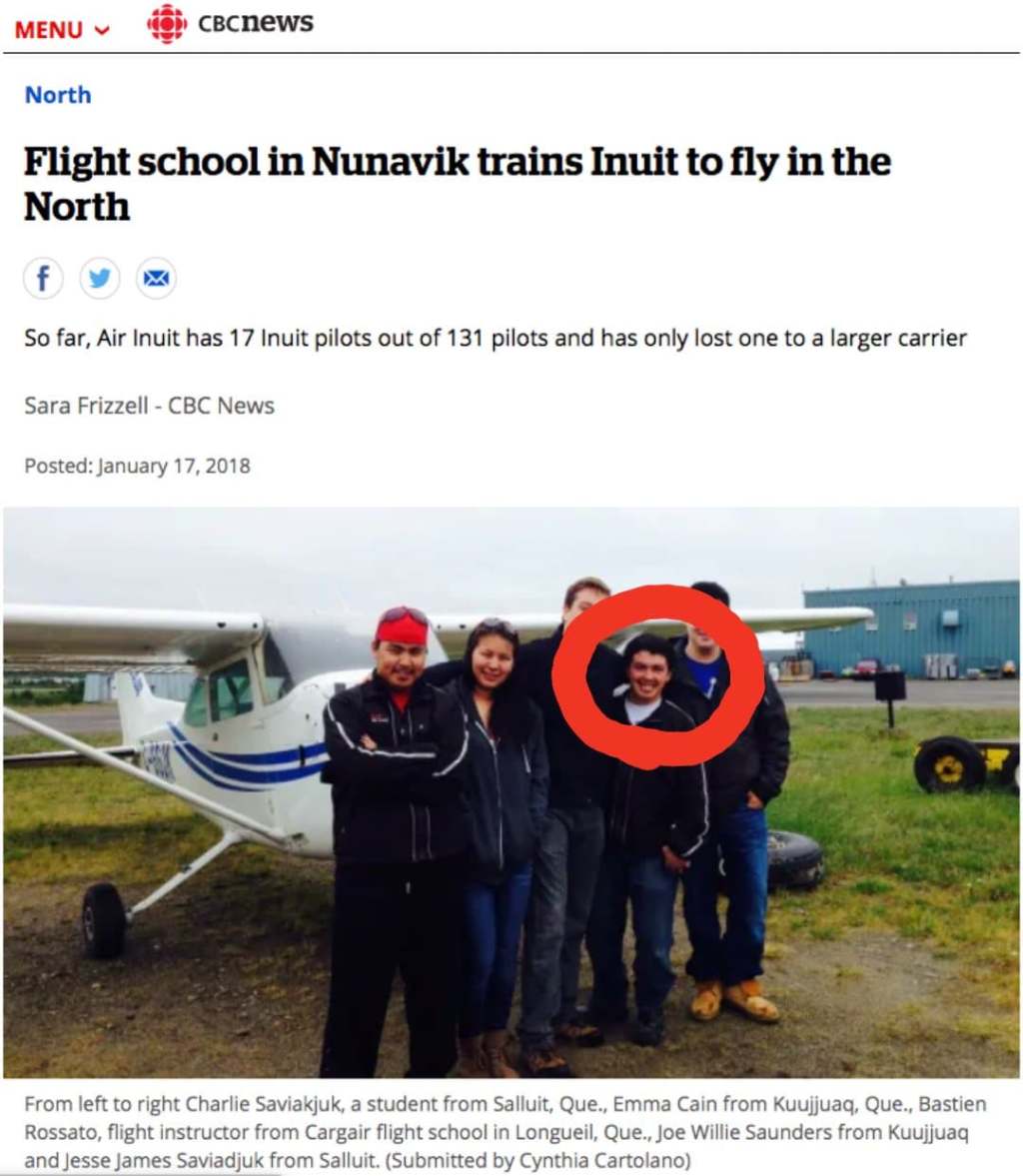

Last year the CBC published a story about Air Inuit hiring and training pilots to help Canada’s on going airline pilot shortage. Air Inuit is based in Montreal and services communities across Nunavik and the North. It’s been running a pilot training program called “The Sparrow Project”; which is funded by the Quebec and Canadian Governments. SHE(BITES) Media has learned that to fill recruit positions, Air Inuit also hired pilots who are convicted rapists and are currently on the National Sex Offender Registry.

Joe Willie Saunders was convicted of rape in 2012 while working as a Constable for the Kativik Regional Police Force. He was on duty when he raped fellow officer Denise Robinson. He was sentenced to 18 months in jail. Denise reported the attack to the force after attempting to “talk it out” with Saunders who responded by stalking and harassing her at night for weeks at her service provided residence. Saunders broke into her home several times subsequent to the rape.

“I was sleeping with my gun, I was not in a good state.” Denise said she was also terrified to report, but couldn’t help but think of all the similar assaults she was being called to in the community she was serving. “He reminded me of all the young women I had helped in similar cases. I had a duty to report this. To protect them. That was the turning point for me, to say how can I ask these other women who are victims to come forward if I don’t report my own assault.”

Denise says she believed in the “brotherhood”, drank the kool-aid and genuinely thought the force would do the right thing and support her after being attacked and assaulted by a colleague. Instead she was told to shut up by the force and her union, who both urged her to sign an NDA and to stop taking action. Colleagues started distancing themselves and she became a target – a problem to get rid of. She was removed from active duty without pay, and was told she was a danger to society. She was locked out of her home, loosing access to her possessions and was even offered money to go away.

Denise pressed on and was under the impression that if Saunders was convicted and her assault was proven in court, that she would be welcomed back by the force.

On the day of trial, Saunders didn’t show up, but plead guilty to a lesser charge – resulting in a sentence of 18 months in jail. Denise was emotional, elated and happy. In a jarring unfolding of events, the force responded to Saunders’ conviction by kicking Denise out of the precinct, and out of the community. “The captain of the police force informed me that I had been trespassed and the sergeant on duty informed him that they wanted me removed immediately. This was 5 minutes after the judge had sentenced Joe Willie. I was not welcome.” She adds, “I was in shock. I was trying not to let it ruin that vindication that I was feeling.”

Denise was then dropped off at the airport only to take the same flight with Saunders back to Montreal (where he was being relocated for his sentence). She was alone and full of fear. The co workers who came to the airport didn’t acknowledge Denise, instead they sent her glares & snide comments. In contrast, they saluted Saunders as they escorted him on the plane. This indicated and revealed to Denise the severity of the boys club cult across Canada’s police agencies. “That’s when I realized this wasn’t over. That my battle was just beginning. It didn’t matter that I won the court case.”

During the same time, the RCMP terminated Denise’s job application process with them, adding that she would not be able to apply with them ever again. No reason was given. Denise now has no pension, no career, and struggles with on going PTSD.

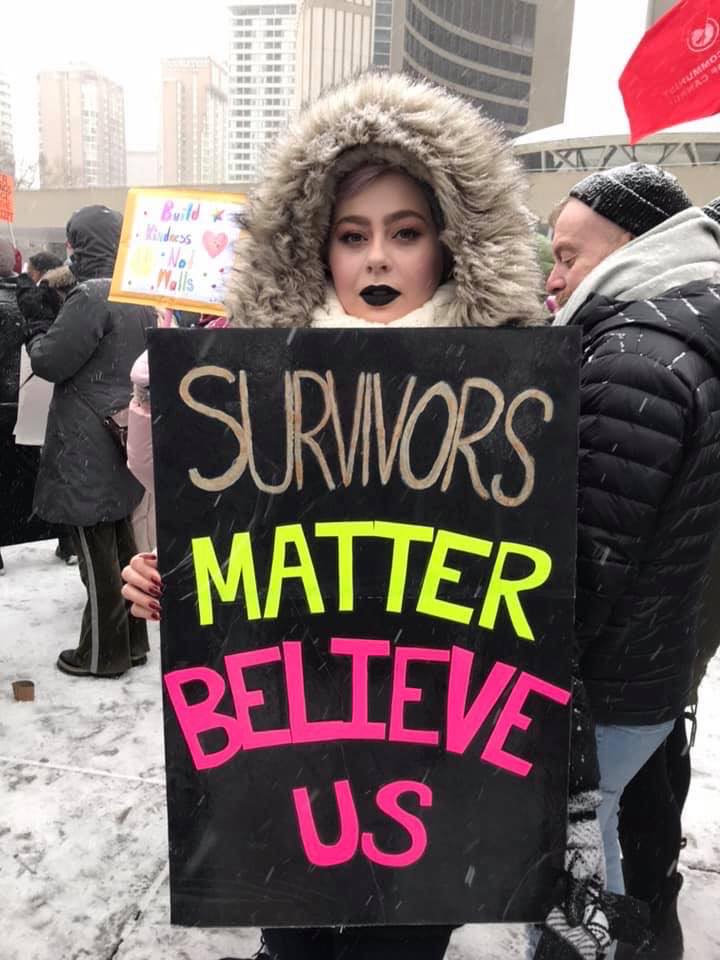

The hardest blows come from sanctuary trauma and institutional betrayal. Denise says women survivors, fighters and whistleblowers across the police force and similar workforces are experiencing the same development. When survivors turn to the entities, groups and people who are supposedly there to help; they are being lied to, failed, rejected, ostracized, and betrayed. Many commit suicide. The reason? PR & Profits.

“Organizations are making decisions based on liability. Based on what’s gonna look bad for them and not about what makes common sense. What does my humanity tell me to do in this situation? When the chips fall they’re not there. That is an illusion. These are very very powerful organizations.” Denise estimates about 70% of the people she knew at the force were complicit, never spoke up, and were easily influenced out of fear of job loss.

Saunders served his time, and through the connections that he has to people in decision making positions in the Nunavik community, has been accepted back into the club.

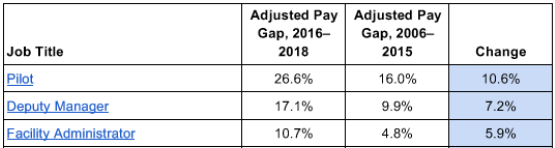

Pilots and police officers are among the top male dominated professions (with the largest gender pay gaps), they are also roles that people have historically looked up to. These positions command respect, and provide an individual with a sense of authority and power.

Denise says that’s exactly why Saunders was attracted to the idea of being a pilot, and that society should be alarmed that sex abuse criminals are able to slip into powerful roles so easily, “It makes me worried. For so long I have forgiven him thinking of excuses – why there were circumstances for him making such a poor choice. And he could have become this pilot and go on with Air Inuit, but he chose to go on the front of a newspaper and glorify what he is doing now. To me that was his mistake. You needed to fluff up your feathers and say ‘Look at me, I’m just as powerful now as a pilot as I was as a police officer! That frightens me.’” To rub the salt in further, Denise herself had been attempting to become a commercial pilot but has not had the funds to fully obtain the flying hours.

The fact is sexual abuse across the airline industry is a rampant and on going problem. WestJet Airlines recently lost it’s third and final appeal attempt against a proposed class action lawsuit with the Supreme Court of Canada. The suit is for breach in contract in failing to keep it’s female flight attendants safe from pilot specific sexual abuse. Air Canada has a human rights complaint against it for sexual objectification. Seemingly, still, no authority can stop pilot behaviour; which ranges from casual sexual harassment and locker room talk, to full blown assault and rape. That’s because they aren’t being held accountable by their corporations and unions (where is ALPA hiding?). In fact, criminals are being protected by those entities.

This is happening because male pilots have a higher value, their status and rank is higher, and they are more expensive to hire and fire. They are a highly desired profession, and they are well protected. Add the fact that there is a country wide pilot shortage and you’ve got a profitable airline #metoovortex, where gingerbread men can get away with their abuse by being passed around from one airline to the other. This gingerbread man phenomena applies to police, learning, entertainment and religious/catholic institutions across the board.

It turns out Saunders didn’t finish his pilot training once he got in with the airline. President of Air Inuit, Pita Aatami, claims he wasn’t responsible for hiring Saunders, and alleges he didn’t know Saunders was a convicted rapist. Aatami provided some answers via email;

“He (Saunders) was on the Sparrow project back in 2014 and he did not finish his course. For your info, Air Inuit was not aware of this persons history.” Aatami adds that it was the community’s school board who was responsible for hiring Saunders, “The Kativik Ilisarniliriniq, this organisation is responsible for all education in Nunavik, they were doing the interviews of all the candidates that were on the Sparrow project.”

Denise was made aware of Saunders’ new pilot position when she read the CBC story in late July. When she saw him on the cover, it sent her into shock, anger, disbelief, and action.

“Now the Government of Canada, Government of Quebec and Makivik Corp are paving the way to get him another position of power? Something is wrong here. I struggle to make ends meet. No pension. No one backing me up.. How do I survive?”

Denise currently has no one in her life, she cannot share her bedroom with anyone, she checks her windows with a level of OCD, most nights she wakes up from night terrors in cold sweats. Her fight or flight is on high alert, and her institutional betrayal is on going. In the end, Denise says a lot of her pain comes from the silence of her female colleagues and friends, and that it was a female Chief (someone she looked up to) who handed her the force’s precinct trespass papers.

Denise points out that women fought hard, and are still fighting to even be accepted in the police force. She says the news about Saunders being hired as a pilot triggered her in a new way, and that her anger is fuelling her action to speak up. She says talking is vital, and that women must start working together more regardless of their background or experience.

“The more I keep talking about it and hearing other women’s stories the more it gives me strength to go on. I cannot let them win. We cannot let them do this. This is our fight, the fight of our generation.”

Saunders is still currently on the National Sex Offender Registry, and will remain there until 2042.

Leave a comment